The enthusiastic campaign to keep Veeraswamy on London’s Regent Street open demonstrates Britain’s well-documented passion for Mulligatawny Soup, chicken tikka and vindaloo. The UK’s oldest Indian restaurant, the Michelin-star Veeraswamy may not reach its centenary next year, because of a lease dispute, however it did start a curry revolution. Moving forward from the stereotypical, and admittedly inauthentic India-inspired baltis and tikkas of the past, regional Indian restaurants are getting increasingly popular. Especially those from Kerala.

Do you know about Virat Kohli’s go-to restaurant when he visits England or plays at the famous Headingley Cricket Ground in the Headingley Stadium complex in Leeds? It’s Tharavadu, a fine-dining restaurant serving authentic Kerala food in the city centre.

Virat Kohli and Anoushka Sharma posing for a photo with Tharavadu staff when they visited Leeds in 2021 during Covid 19 pandemic

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Siby Jose, who co-founded Tharavadu with Prakash Mendonca, Ajith Kumar, Rajesh Nair and Manoharan Gopal says that the restaurant, rose to the front burner of fame in September 2014, just a couple of months after its launch. “The Indian team was here for a tournament and they were staying at the Marriott Hotel, just across the road from Tharavadu. MS Dhoni wanted South Indian breakfast for the team. However, the Pakistani chef at the hotel was not familiar with South Indian cuisine. So, we went to the hotel early in the morning with dosa batter and made fresh dosas along with sambhar and chutney for the team,” he recalls.

Tharavadu was featured four consecutive times (2016-2019) in the Michelin Restaurant Guide, and was included in the Top 100 UK restaurants of 2023 and 2024 by SquareMeal

| Photo Credit:

Aswin VN

Soon after, Sanju Samson visited the restaurant, and then Kohli dropped in. Since then, Tharavadu is frequented by the Indian cricket team every time they play a match in Leeds. The restaurant has also hosted Kohli and Anushka Sharma during 2019 ICC Cricket World Cup and in 2021 India tour of England.

One of the signed customer reviews displayed at Tharavadu

| Photo Credit:

Aswin VN

Lack of familiarity

The archetypal Indian restaurant in the UK has always been a place that serves curries in a narrow range of bases — tikka masala, karahi, jalfrezi, balti, vindaloo and so on — forming the bulk of what is popularly known as British-Indian cuisine.

Porotta and Kozhi Kurumulagu served at Tharavadu

| Photo Credit:

Aswin VN

Although there are restaurants now, mostly in big cities, that focus on delivering more authentic dishes, most of them focus on Delhi or Punjabi cuisines, or popular street specialties, such as chaat, channa bhatura and vada pav. South Indian restaurants are few and far between, and that includes Sri Lankan restaurants that serve dishes popular in South Indian states as well.

Kozhi Kurumulagu made using fresh green peppercorns, a special dish of Tharavadu

| Photo Credit:

Aswin VN

Britain is still largely unfamiliar with the food of Kerala, even though it has a a significant population of people from the state. So, Siby’s and his team have to constantly explain how diverse India is to local customers. “That’s the reason why we have a map of the country here to explain that India is such a big country, and every state has its own style of curries and ingredients,” Siby says, pointing to the big map of India behind him on the wall. Maps of each district in Kerala are also on the walls of Tharavadu.

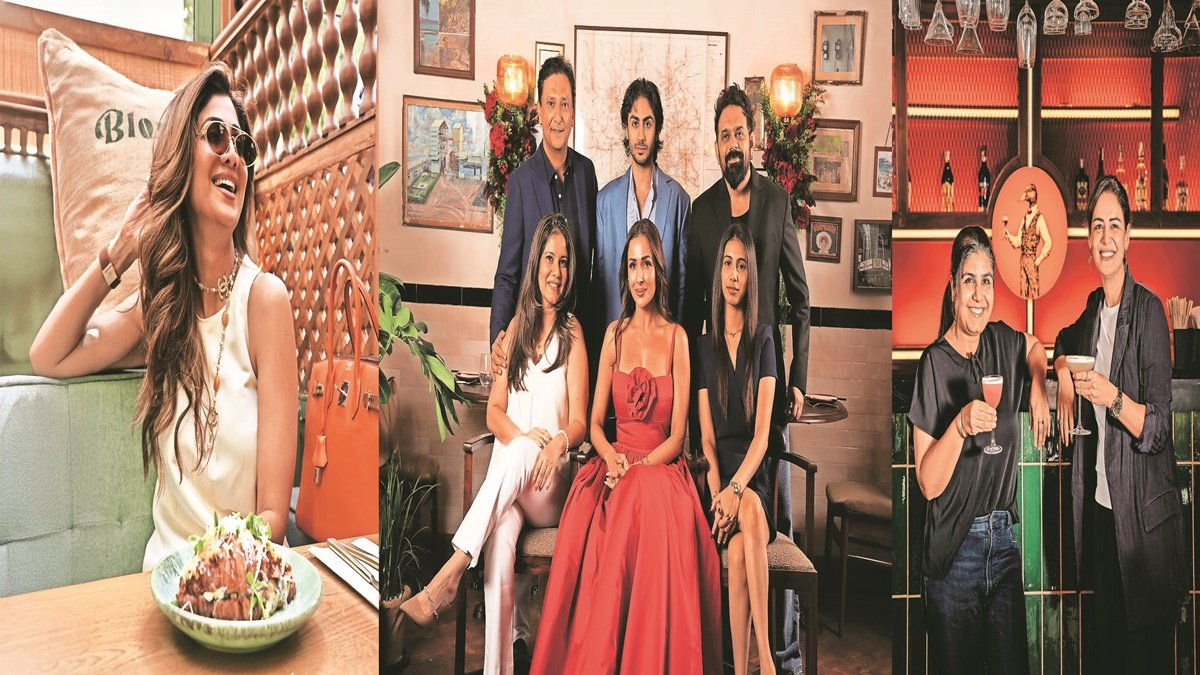

Kayal restaurant in Leicester

| Photo Credit:

Aswin VN

For the same reason, Kayal restaurant’s Leicester branch houses two television sets that play visuals of cultural aspects of Kerala on a loop. “The TV was the first thing that we installed when we started this restaurant 20 years back. When other British restaurants used the TV to show sporting events, we wanted to introduce our customers to the land where this food was coming from,” says Jaimon Thomas, who is the founder and owner of Kayal and its sister restaurants across England. Kayal has three branches, one each in Nottingham, Leamington Spa and West Byfleet. They also have a branch in Melbourne, Australia. The restaurant chain has a franchising program too.

Sea Bass Mappas and Appam served at Kayal restaurant

| Photo Credit:

Aswin VN

“Kerala cuisine was a real discovery for many people in Leicester when we first opened it. I couldn’t believe that customers were queuing up within a few weeks of the opening. Many people were coming from other parts of UK to try our food,” Jaimon recalls.

Balancing spices and courses

While local crowds are used to the medium-spice levels of British-Indian cuisine, there is a question of how they might respond to Kerala dishes, which can contain chilli pepper, bird’s-eye green chillies, red chilli powder and black pepper.

Kunji Njandu Vattichathu, a softshell crab dish served at Tharavadu

| Photo Credit:

Aswin VN

The trick is to cook as per the spice tolerance of the local crowd, while retaining the original flavours of the recipes. “We retain the authenticity of the Kerala cuisine while reducing the spice levels a bit, and we don’t skip any of the ingredients such as kokum or chillies (that make our dishes unique). We even export green pepper corns from Kerala for certain recipes. For instance, kozhi kurumulagu is a chicken dish made with fresh pepper. We make special chicken stock and infuse it with the flavours of pepper corns and other ingredients without over-spicing it,” explains Ajith Kumar, the executive chef at Tharavadu.

King Prawns dish served at Tharavadu

| Photo Credit:

Aswin VN

Designing the menu in a European-course-meal style is another way in which Kerala restaurants have been catering to locals’ preferences. The Kayal restaurant is a trendsetter in this regard as it was one of the first restaurants in the UK to present the Kerala cuisine in a course-meal structure that several other Kerala restaurants follow today. “So, we have a three-course menu with starters, main course items and desserts. When deciding the starters, the first thing that came to my mind was beef ullarthiyathu that my mom used to make for dad to have with his drink. Likewise, the banana boli that we have as an afternoon snack in Kerala is a starter for us here,” Jaimon says.

Selling point

There are exceptions too — not everything has to cater to the British palate. Saji Kurian, veteran chef of Kalpakavadi restaurant, which was launched in 2019 in the old city of York, says the spicy-tangy fish dishes of Kerala sell the most. He adds that they make fish curries just like they do at home in Kerala in an earthen vessel, without compromising on spice levels, only adjusting them when someone asks. “Kappa (tapioca) and naadan fish curry is probably the most popular choice here. Meen pollichathu sells a lot as well. We use a whole sea bass for that, then stuff it with prawns and roast it in a banana leaf,” he explains.

Kalpakavadi restaurant in York

| Photo Credit:

Aswin VN

It’s the same story at Tharavadu and Kayal. Kerala’s backwater delicacies are all the rage, and the flaky, fluffy Kerala porotta is a big hit with locals. “We did a bit of research, and found that meen kootaan (fish curry) with porotta is the most-ordered dish. On an average, we sell around 300 porottas every day. We got a chef only for that dish,” adds Siby.

At Kayal, the seafood platter, comprising squid rings, mussels, prawns and fish fillet, marinated and fried in Kerala style, is an extremely popular starter, and so is the pepper-packed salmon mappas with fluffy appams.

Kerala vegan options

While seafood and other non-veg dishes sell the most, many health and climate-conscious customers are also finding vegan and gluten-free options in Kerala cuisine attractive. Apart from the obvious options, such as thorans (sauteed vegetables with grated coconut) and vegetable-based dishes that are staple to Kerala cuisine, chefs are improvising to create new dishes. “Although we had quite a few gluten-free main course options, we did not have anything in the desserts that those allergic to gluten can have. So, we came up with a dessert called vattayappam fudge cake, using Kerala’s own sweet rice-cake, vattayappam. It’s made by filling vattayappam with a syrup made of butter cream and brown sugar, and then pouring chocolate sauce over it. In our next menu, we are going to introduce a cream-caramel based dessert using kinnathappam (another sweet rice-cake) for those with dairy-allergy,” explains chef Ajith.

Vegan restaurant Herb in Leicester

| Photo Credit:

Aswin VN

This demand for vegan food drove Kayal group to even start a dedicated vegan restaurant called Herb in 2017, in Leicester. “We have staple vegan dishes in our cuisine, and we were noticing that a lot of our customers were coming here just for our vegan options. So, when veganism became a trend some years back, we decided to start a vegan restaurant for fine dining”, says Jaimon. A cursory look at the Herb menu shows how diverse the cuisine can be and how flexible it is to improvisation with creations such as green papaya stew and jackfruit ularthiyathum kadala curryum (Slow-roasted jack fruit with chickpea curry).

This flexibility, to be able to cater to drastically different food preferences with a variety of authentic veg and non-veg options, is what helps Kerala restaurants stand apart in the highly competitive Indian restaurant market of the UK. With more and more Kerala restaurants opening across the UK every year, it is clear that the cuisine is becoming a mainstay of the British culinary scene.