Solo Travellers

Explore Portugal’s historic hilltop hamlets in a free electric hire car | Portugal holidays

Twisting along roads flanked by cherry trees, granite boulders, vines and wildflower-flecked pastures, I wind down the windows and breathe in the pure air of Portugal’s remote, historic Beira Interior region. The motor is silent, the playlist is birdsong and occasional bleating sheep; all is serene. “This is easier,” I say to myself with a smile, recalling my previous attempt to visit the Aldeias Históricas – a dozen historic hamlets bound by a 1995 conservation project – using woeful public transport. Revisiting this unspoilt pocket of Portugal, 155 miles (250km) north-east of Lisbon, near the border with Spain, is going to be effortless in an EV. And, best of all, the transport doesn’t cost me a penny.

An hour before, I arrived in Castelo Novo, a four-hour train ride from the capital, and currently the sole hub of the Aldeias Históricas’s Sustainable Urban Mobility Scheme. It was launched in 2022 to address local transport issues by providing five free-to-hire electric vehicles, alongside other community-supporting projects. It sounded too good to be true, but I booked the maximum three-day rental – enough time to see at least nine of the villages. I was informed that if I arrived by train, someone would meet me at the station.

Sure enough, Duarte Rodrigues welcomes me like an old friend. “The project’s main focus is tourism to the historic villages, but some of the cars are used for the community, to take elderly people to the market or distribute meals,” he says on the gorgeous drive to the medieval hamlet of Castelo Novo, 650 metres up the slopes of the Serra da Gardunha. Take-up was nearly equal between tourists and residents, he adds.

A few minutes later, outside the romanesque town hall, Duarte hands me the keys to my Megane E-Tech with a wave. It’s worth staying for a night at Pedra Nova, a gorgeously renovated boutique B&B, but it needs to be booked well in advance and I am keen to make the most of my time in the EV. Having decided to skip popular Piódão and Monsanto – now a House of the Dragon jet-setting destination – my first stop is Belmonte. Like all 12 aldeias, this hazy hilltop town played a pivotal role in Portugal’s identity. A Brazilian flag flutters behind a statue of local legend Pedro Álvares Cabral, the first European to “discover” Brazil. I stroll through the old Jewish Quarter’s single-storey granite houses to Bet Eliahu synagogue, built 500 years after King Manuel I’s 1496 decree expelling Jews from the kingdom.

Continuing to 12th-century Linhares da Beira, I wander the leafy slopes of the Serra da Estrela – mainland Portugal’s highest range. Similar to much-loved Monsanto, the hamlet lies between and atop giant granite boulders. From the largest rocky outcrop, where the castle’s crenellated walls rise, the Mondego valley’s panorama is endless. Other than an airborne paraglider and a man hawking hand-carved magnets in the car park, there’s not a soul in sight.

I walk a stretch of slabbed Roman road that once linked Mérida in Spain to Braga, north of Porto, and remember why I adore these villages. History is bite-size, hushed and unhurried, the antithesis of my home in the Algarve. After a brief drive, I park up and plug in outside the medieval defences of the most populated aldeia.

Founded in the ninth century, handsome Trancoso hides behind hefty, turret-topped walls that have witnessed royal nuptials and numerous skirmishes. Today, walking beneath weathered porticos and streets lined with hydrangeas, it feels like the calmest place in the world. As does Solar Sampaio e Melo, a palatial 17th-century guesthouse – repurchased by a descendant of the original owners in 2011 – with an honesty bar and a pool shaded by turrets.

Following a late breakfast of sardinhas doces, Troncoso’s sardine-shaped, almond-stuffed sweets, I make for Marialva. The satnav states 30 minutes, but with back-road detours to gawp at giant granite mounds around Moreira de Rei, I reach the massif-mounted castle well after lunch. Occupied by the Aravos, a Lusitanian tribe, then the Romans and Moors, this was a crucial site for the advance of the Christian Reconquista.

An old chap in a checkered shirt sits hammering almonds from their shells outside his home. I buy a bulging bag for €7 and gobble a handful inside the semi-ruined citadel, where Bonelli’s eagles soar and cacti reclaim the stone. The flavour transports me to my Algarvian childhood holidays, when I’d hide from the sun (and my parents) under almond trees. For a second, it feels like Portugal hasn’t changed in 30 years. Perhaps here, far from the coast, little has.

The journey to Castelo Rodrigo is filled with awe, particularly around the craggy valley sliced by the Côa river. Just upstream is a unique collection of rock art etchings from three eras – prehistory, protohistory and history – and Faia Brava, Portugal’s first private nature reserve, co-founded by biologist Ana Berliner, her husband and others. In 2004, the couple renovated Casa da Cisterna into a boutique guesthouse, and on its wisteria-draped terrace, Ana welcomes me with sugared almonds and fresh juice. I enquire about Faia Brava (Ana guides guests on excursions to the reserve and the prehistoric rock art) and whether they’re concerned about tourism growing.

“These small villages benefit a lot [from tourism] because there aren’t many people living here or many opportunities, so people are moving to the big cities,” she tells me. “If you retain your people, and your young people spend those days living here, it’s very good.”

As I poke around the castle ruins, I mull over how the Portuguese writer José Saramago described Castelo Rodrigo in Journey to Portugal (1981): “desolation, infinite sadness” and “abandoned by those who once lived here”. I’m reassured that Ana is right. Lisbon’s tourism boom has created Europe’s least affordable city for locals. Yet, in these hinterlands, the right tourism approach could help preserve local customs.

Unlike most of the aldeias, Castelo Rodrigo was founded by the Kingdom of León. It became Portuguese when the 1297 treaty of Alcanizes defined one of Europe’s oldest frontiers. Reminders of Spain linger, such as the Ávila-style semicircular turrets and ruined Cristóvão de Moura palace, constructed under the Habsburg Spanish kings. Portuguese locals later torched it.

With no charging station in Castelo Rodrigo (work is under way to expand the project to other villages, including the installation of chargers and the opening of new bases with additional cars in 2026), I drive to Figueira de Castelo Rodrigo, the modern town below. At Taverna da Matilde flaming chouriço scents the dining room, and the pork loin – bisaro, an indigenous part-pig, part‑boar – is perfect. I sleep like a prince at Casa da Cisterna.

Breakfast is a casual, communal affair of buttery Seia mountain cheese and pão com chouriço, followed by a quick stop at Castelo Rodrigo’s wine cooperative to collect a case of robust Touriga Nacional (tours and tastings €18pp). In Almeida, a star-shaped military town, I roam the grassy ramparts before continuing south. Swallows soon replace eagles, and granite fades into gentle farmland.

I breathe in the silence, standing by Castelo Mendo’s twin-turreted gate. It feels like the world has stopped. I tiptoe across the ruined castle keep and am transfixed by the endless panorama of olive groves, cherry trees and occasional shepherd’s huts.

In search of coffee, I step into a dimly lit stone room below a sign that reads D Sancho. Inside is an old-world retail marvel. Photos of popes, boxes of wine, retired horseshoes, mounds of old coins and “mystery boxes” that I’m tempted to spend a tenner on. A hunched woman with a smile gifts me a shot of ginjinha, the local cherry liquor, and signals me to sit with her on the bench outside. We don’t speak, yet I somehow feel a connection to her land. I buy a bottle in the hope of taking that feeling home.

My final stop, Sortelha, comes with high expectations – Saramago promised a perfectly preserved medieval town. Hulking walls cradle a 16th-century cluster of stone houses dominated by a castle that crowns an outcrop. Almost on cue, fog and showers shroud it all in mystery. I retreat to O Foral, where plates of bacalhau (salted cod) are bathed in pistachio-hued local olive oil.

Parking back in Castelo Novo with a panic-inducing 7% charge showing on the dash, I am grateful to return the keys, and use the time before my lift to the station to survey the Knights Templar’s former domain from the 12th-century castle.

Stopping outside the red door where Saramago reportedly once stayed, I ponder how he would describe these villages 44 years later. Hopefully, he’d recount that, for the traveller, timeless magic remains, but those returning and reviving have vanquished any melancholy.

Complimentary EV rentals of one to three days can be booked online at plataformaaldeiashistoricas.com; reservations open about 75 days in advance. For details of the 12 Aldeias Históricas, visit aldeiashistoricasdeportugal.com

Solo Travellers

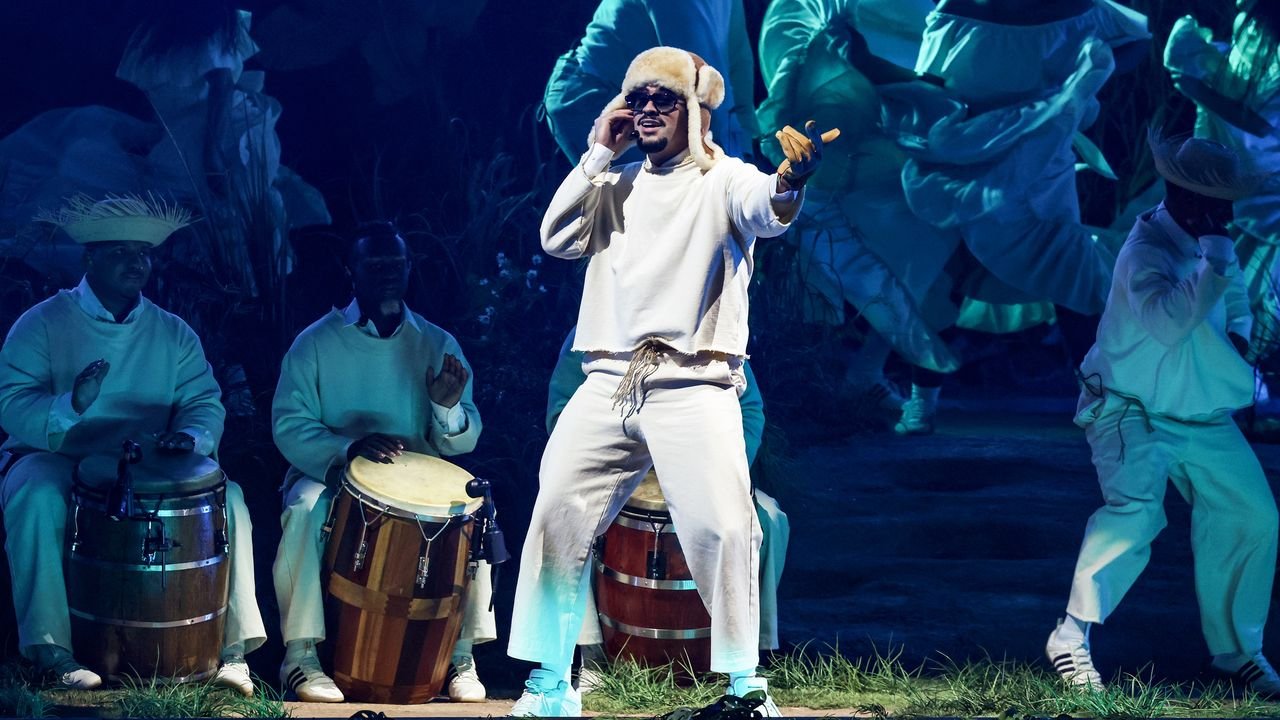

A Bad Bunny Puerto Rico Guide Inspired By the Megastar’s Island Residency

Recommended listening: “Nuevayol.” La Disquera once served as the San Juan office for Fania Records, the pioneering salsa label founded in New York City—the city Bad Bunny sings about in the namesake song (with a fabulous sample of salsa hit “Un Verano en Nueva York”). At El Choli, keep an eye open for a pop-up of Toñitas, the iconic Boricua bar in Brooklyn that he name checks in the song.

La Factoría cocktail bar

A day tour of Old San Juan is practically mandatory for any first-time visitor; but stay a little while after dark to see it come alive. La Factoría is famed for its crafty cocktails, as well as the labyrinthine setup of the space. There are multiple rooms to peruse, each with its own style of music and dance; in the largest, you’ll find locals and visitors mingling on the dance floor to salsa, merengue, and bachata, while other rooms offer electronic music and reggaetón on the weekends. There’s even a special enclave for the lovers and the introverts, who may appreciate the intimacy of a low-lit and low-volume space.

Recommending listening: “Baile Inolvidable.” There are no salsa dance classes to be found here—just feel the rhythm and find your own way.

Lala restaurant

Trip to the mall, anyone? Beyond the Nordstrom and Tiffany’s, inside the ritzy Mall of San Juan is an upscale Puerto Rican dining experience worth the hype. Partially owned by Bad Bunny and his manager, Noah Assad, the picturesque restaurant boasts a globetrotting experience encapsulated in its menu. It’s ideal for those traveling in groups with conflicting palettes; at Lala, one friend’s craving for pan-fried gyoza and hamachi can peacefully co-exist with another’s hankering for sweet corn agnolotti.

Recommended listening: “Perfumito Nuevo.” Be like Bad Bunny’s co-star RaiNao—get dressy, try out that new perfume you just bought.

Manzana de Java restaurant

“We believe that Puerto Rico, and the Caribbean, have more in common with Southeast Asia than people think,” says Juan Camilo Becerra, manager of Manzana de Java: an Antillean-meets-Asian fusion kitchen, located two blocks south of the Playa del Pueblo. Repurposed from an old ramen shop, this one-of-a-kind restaurant fashions tapas from the intersections of two tropical regions. Highlights from the menu include ceviche served in a cacao pod, lionfish chicharrones served with a green curry aioli, and a goat meat fricasse with tamarind and cashews.

Recommended listening: “Voy a Llevarte a PR.” Much like the song, which Bad Bunny dedicates to a faraway love interest, Manzana de Java is both sweet and spicy.

La Placita de Santurce

What appears to be a farmer’s market during the week transforms into a full-on bacchanal on the weekends. Nestled in the neighborhood of Santurce, this plaza is lined with bars blasting reggaetón—and the people spilling out of them to dance in the cobblestone streets. Start your night with Caribbean snacks at Jungle Bird and roam as you wish. On one block, you’ll find whole families singing karaoke outdoors; around the corner, you’ll see old men drinking beer, playing dominoes, and watching salsa videos on a big-screen TV. There’s also an abundance of murals to take drunken photos with, including a special Bad Bunny portrait celebrating his role in Puerto Rican music and culture.

Recommended listening: “Debí Tirar Más Fotos.” This is Puerto Rico at its best; in music, food and community.

Solo Travellers

‘Unlike anywhere else in Britain’: in search of wildlife on the Isles of Scilly | Isles of Scilly holidays

At Penzance South Pier, I stand in line for the Scillonian ferry with a few hundred others as the disembarking passengers come past. They look tanned and exhilarated. People are yelling greetings and goodbyes across the barrier. “It’s you again!” “See you next year!” A lot of people seem to be repeat visitors, and have brought their dogs along.

I’m with my daughter Maddy and we haven’t got our dog. Sadly, Wilf the fell terrier died shortly before our excursion. I’m hoping a wildlife-watching trip to the Isles of Scilly might distract us from his absence.

One disembarking passenger with a cockapoo and a pair of binoculars greets someone in the queue. “We saw a fin whale,” I hear him say. “Keep your eyes peeled.”

This is exciting information. The Scillonian ferry is reputedly a great platform for spotting cetaceans and it’s a perfect day for it – the sea is calm and visibility is superb. From the deck, the promontory that is Land’s End actually seems dramatic and special, in a way that it doesn’t from dry land. There are several people armed with scopes and sights who are clearly experienced and observant. The only thing lacking is the animals. Not a single dolphin makes an appearance, never mind the others that make regular summertime splashes: humpbacks, minke, sunfish, basking sharks and, increasingly, bluefin tuna.

Arriving in Scilly by ship is worth the crossing: wild headlands, savage rocks, white sand beaches, sudden strips of transcendentally turquoise ocean interspersed with the bronzed pawprints of kelp. Of course, it can be thick mist and squalls, but we’re in luck, the islands are doing their best Caribbean impersonation. Hugh Town, the capital of St Mary’s, is built on the narrow isthmus between two rocky outcrops. It’s a quirky, independent town with the kind of traffic levels our grandparents would recognise.

Up the hill, from the terrace of the Star Castle Hotel, we can see all the islands spread out around us, and handily there’s a lady with a friendly labrador who gives us a pithy summary of each. St Martin’s: “Beach life.” Tresco: “The royals love it.” St Agnes: “Arty.” Bryher: “Wild and natural.”

Bryher is our big wildlife destination because the plan is to rent kayaks there and paddle to the uninhabited Samson island, which is a protected wildlife area. I’m banking on Samson for wildlife now that the whales didn’t show up, but first we’re going to explore St Agnes with Vickie from the Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust.

After a short ferry ride from St Mary’s quay, we stroll around St Agnes and across a short sand spit, a tombolo, to its neighbour, Gugh. Vickie leads us up a heather-covered hillside next to an impressive stack of pink granite boulders. “St Agnes and Gugh used to have a rat problem,” she tells us. “There were an estimated 4,000 that had destroyed the breeding populations of both Manx shearwaters and storm petrels. We’re pretty sure we’ve eradicated them now and the bird populations are rising fast.”

She leans over a small burrow under a lichen-crusted rock, and sniffs. “Yes, that’s storm petrel – they have a distinctive aroma.” Using her phone, she plays a series of cackles and squeaks down the hole. No response.

I ask Vickie about the archipelago’s endemic species. The Scilly bee? “Hasn’t been seen for many years.” She chuckles. “What makes the islands special is often what we don’t have. There are no magpies or buzzards, no foxes or grey squirrels. Those absences are important.”

What they don’t have in terms of fauna, they certainly make up for in flora. The lanes and paths of St Agnes are a ravishing spectacle: agapanthus and honeysuckle, huge spires of echium and smooth succulent aeoniums from the Canary Islands. In this frost-free environment, all kinds of subtropical plants thrive, making the islands quite unlike anywhere else in the British Isles. Dotted among all this fecundity are artists’ studios, galleries, a pub and a community hall where there’s a wonderful display of shipwreck souvenirs: East India Company musket parts, skeins of silk, porcelain and perfume.

Back on St Mary’s, we swim and spot a seal. But if we imagine our luck is changing, it’s not. Next morning we are down on the quayside, bright and early for the boat to Bryher. “It just left,” says the ticket seller. “We did post the change last night. Very low tide. Had to leave 15 minutes early.”

“When is the next one?”

“There isn’t one.”

The islands, I should have known, are run by the tides. Be warned.

Without any time to think, we jump on the Tresco boat. A fellow passenger offers sympathy. “Last week we missed the boat from St Martin’s and had to spend the night there. It was great.”

after newsletter promotion

I relax. She is right. The best travel adventures come unplanned.

The low tide means we land at Crow Point, the southern tip of Tresco. “Last return boat at five!” shouts the boatman. We wander towards a belt of trees, the windbreak for Tresco Abbey Garden. The eccentric owner of the islands during the mid-19th century, Augustus Smith, was determined to make the ruins of a Benedictine abbey into the finest garden in Britain. Having planted a protective belt of Monterey pine, his gardeners introduced a bewildering array of specimen plants from South Africa, Latin America and Asia: dandelions that are three and a half metres tall, cabbage trees and stately palms. Just to complete the surreal aspect, Smith added red squirrels and golden pheasants, which now thrive.

Now comes the moment, the adventure decision moment. I examine the map of the island and point to the north end: “It looks wilder up there, and there’s a sea cave marked.”

We set off. Tresco has two settlements: New Grimsby and Old Grimsby, both clutches of attractive stone cottages decked with flowers. Beyond is a craggy coast that encloses a barren moorland dotted with bronze age cairns and long-abandoned forts. At the north-eastern tip we discover a cave high on the cliffside. Now the low tide is in our favour. We clamber inside, using our phone torches. A ramp of boulders takes us down into the bowels of the Earth, and to our surprise, where the water begins, there is a boat, with a paddle. Behind it the water glitters, echoing away into absolute darkness.

We climb in and set off. Behind us and above, the white disc of the cave entrance disappears behind a rock wall. The sound of water is amplified. After about 50 metres we come to a shingle beach. “How cool is that?” says Maddy. “An underground beach.”

We jump out and set off deeper into the cave, which gets narrower and finally ends. On a rock, someone has placed a playing card: the joker.

Later that day, having made sure we do not miss the last boat back, we meet Rafe, who runs boat trips for the Star Castle Hotel. He takes pity on us for our lack of wildlife. “Come out on my boat tomorrow morning and we’ll see what we can find.”

Rafe is as good as his word. We tour St Martin’s then head out for the uninhabited Eastern Isles. Rafe points out kittiwakes and fulmars, but finally we round the rock called Innisvouls and suddenly there are seals everywhere, perched on rocks like altar stones from the bronze age. “They lie down and the tide drops,” says Rafe. “These are Atlantic greys and the males can be huge – up to 300kg.”

Impressive as the seals are, the islands are better known for birds, regularly turning up rarities. While we are there, I later discover, more acute observers have spotted American cliff swallows that have drifted across the Atlantic, various unusual shearwater species and a south polar skua.

Next day is our return to Penzance, and it’s perfect whale-watching weather. People are poised with binoculars and scopes, sharing tales of awesome previous sightings: the leaping humpbacks, the wild feeding frenzies of tuna, and the wake-riding dolphins. Nothing shows up. I complain, just a little, about our lack of wildlife luck. Maddy is playing with a pair of terriers. “The thing with Wilf was he was always content with whatever happened,” she says. I lounge back on the wooden bench on the port side, enjoying the wind, sun and sound of the sea. I’m channelling the spirit of Wilf. Be happy. Whatever. It’s a lovely voyage anyway. And that’s how I missed the sighting of the fin whale off the starboard side.

The Star Castle Hotel on St Mary’s has double rooms from £249 half-board off-season to £448 in summer; singles from £146 to £244. Woodstock Ark is a secluded cabin in Cornwall, handy for departure from Penzance South Pier (sleeps two from £133 a night). The Scillonian ferry runs March to early November from £75pp. Kayak hire on Bryher £45 for a half day, from Hut 62. For further wildlife information check out the ios-wildlifetrust.org.uk

Solo Travellers

Freedom With Purpose and Poetry on Roads | Ranchi News

-

Brand Stories6 days ago

Brand Stories6 days agoBloom Hotels: A Modern Vision of Hospitality Redefining Travel

-

Brand Stories1 day ago

Brand Stories1 day agoCheQin.ai sets a new standard for hotel booking with its AI capabilities: empowering travellers to bargain, choose the best, and book with clarity.

-

Destinations & Things To Do7 days ago

Destinations & Things To Do7 days agoUntouched Destinations: Stunning Hidden Gems You Must Visit

-

AI in Travel7 days ago

AI in Travel7 days agoAI Travel Revolution: Must-Have Guide to the Best Experience

-

Brand Stories3 weeks ago

Brand Stories3 weeks agoVoice AI Startup ElevenLabs Plans to Add Hubs Around the World

-

Brand Stories2 weeks ago

Brand Stories2 weeks agoHow Elon Musk’s rogue Grok chatbot became a cautionary AI tale

-

Destinations & Things To Do1 day ago

Destinations & Things To Do1 day agoThis Hidden Beach in India Glows at Night-But Only in One Secret Season

-

Asia Travel Pulse3 weeks ago

Asia Travel Pulse3 weeks agoLooking For Adventure In Asia? Here Are 7 Epic Destinations You Need To Experience At Least Once – Zee News

-

AI in Travel3 weeks ago

AI in Travel3 weeks ago‘Will AI take my job?’ A trip to a Beijing fortune-telling bar to see what lies ahead | China

-

Brand Stories3 weeks ago

Brand Stories3 weeks agoChatGPT — the last of the great romantics

You must be logged in to post a comment Login