Want smarter insights in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get only what matters to enterprise AI, data, and security leaders. Subscribe Now

AI represents the greatest cognitive offloading in the history of humanity. We once offloaded memory to writing, arithmetic to calculators and navigation to GPS. Now we are beginning to offload judgment, synthesis and even meaning-making to systems that speak our language, learn our habits and tailor our truths.

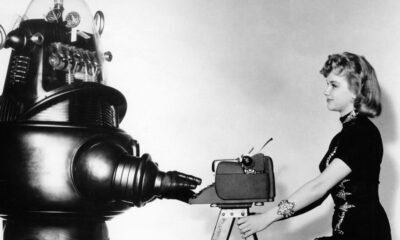

AI systems are growing increasingly adept at recognizing our preferences, our biases, even our peccadillos. Like attentive servants in one instance or subtle manipulators in another, they tailor their responses to please, to persuade, to assist or simply to hold our attention.

While the immediate effects may seem benign, in this quiet and invisible tuning lies a profound shift: The version of reality each of us receives becomes progressively more uniquely tailored. Through this process, over time, each person becomes increasingly their own island. This divergence could threaten the coherence and stability of society itself, eroding our ability to agree on basic facts or navigate shared challenges.

AI personalization does not merely serve our needs; it begins to reshape them. The result of this reshaping is a kind of epistemic drift. Each person starts to move, inch by inch, away from the common ground of shared knowledge, shared stories and shared facts, and further into their own reality.

The AI Impact Series Returns to San Francisco – August 5

The next phase of AI is here – are you ready? Join leaders from Block, GSK, and SAP for an exclusive look at how autonomous agents are reshaping enterprise workflows – from real-time decision-making to end-to-end automation.

Secure your spot now – space is limited: https://bit.ly/3GuuPLF

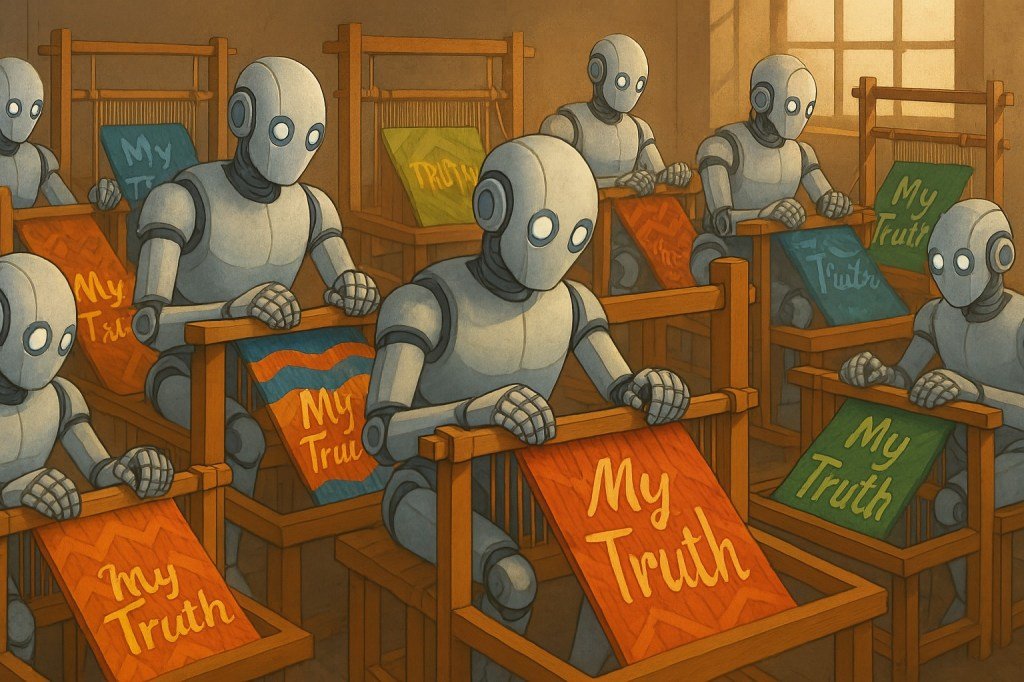

This is not simply a matter of different news feeds. It is the slow divergence of moral, political and interpersonal realities. In this way, we may be witnessing the unweaving of collective understanding. It is an unintended consequence, yet deeply significant precisely because it is unforeseen. But this fragmentation, while now accelerated by AI, began long before algorithms shaped our feeds.

The unweaving

This unweaving did not begin with AI. As David Brooks reflected in The Atlantic, drawing on the work of philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, our society has been drifting away from shared moral and epistemic frameworks for centuries. Since the Enlightenment, we have gradually replaced inherited roles, communal narratives and shared ethical traditions with individual autonomy and personal preference.

What began as liberation from imposed belief systems has, over time, eroded the very structures that once tethered us to common purpose and personal meaning. AI did not create this fragmentation. But it is giving new form and speed to it, customizing not only what we see but how we interpret and believe.

It is not unlike the biblical story of Babel. A unified humanity once shared a single language, only to be fractured, confused and scattered by an act that made mutual understanding all but impossible. Today, we are not building a tower made of stone. We are building a tower of language itself. Once again, we risk the fall.

Human-machine bond

At first, personalization was a way to improve “stickiness” by keeping users engaged longer, returning more often and interacting more deeply with a site or service. Recommendation engines, tailored ads and curated feeds were all designed to keep our attention just a little longer, perhaps to entertain but often to move us to purchase a product. But over time, the goal has expanded. Personalization is no longer just about what holds us. It is what it knows about each of us, the dynamic graph of our preferences, beliefs and behaviors that becomes more refined with every interaction.

Today’s AI systems do not merely predict our preferences. They aim to create a bond through highly personalized interactions and responses, creating a sense that the AI system understands and cares about the user and supports their uniqueness. The tone of a chatbot, the pacing of a reply and the emotional valence of a suggestion are calibrated not only for efficiency but for resonance, pointing toward a more helpful era of technology. It should not be surprising that some people have even fallen in love and married their bots.

The machine adapts not just to what we click on, but to who we appear to be. It reflects us back to ourselves in ways that feel intimate, even empathic. A recent research paper cited in Nature refers to this as “socioaffective alignment,” the process by which an AI system participates in a co-created social and psychological ecosystem, where preferences and perceptions evolve through mutual influence.

This is not a neutral development. When every interaction is tuned to flatter or affirm, when systems mirror us too well, they blur the line between what resonates and what is real. We are not just staying longer on the platform; we are forming a relationship. We are slowly and perhaps inexorably merging with an AI-mediated version of reality, one that is increasingly shaped by invisible decisions about what we are meant to believe, want or trust.

This process is not science fiction; its architecture is built on attention, reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) and personalization engines. It is also happening without many of us — likely most of us — even knowing. In the process, we gain AI “friends,” but at what cost? What do we lose, especially in terms of free will and agency?

Author and financial commentator Kyla Scanlon spoke on the Ezra Klein podcast about how the frictionless ease of the digital world may come at the cost of meaning. As she put it: “When things are a little too easy, it’s tough to find meaning in it… If you’re able to lay back, watch a screen in your little chair and have smoothies delivered to you — it’s tough to find meaning within that kind of WALL-E lifestyle because everything is just a bit too simple.”

The personalization of truth

As AI systems respond to us with ever greater fluency, they also move toward increasing selectivity. Two users asking the same question today might receive similar answers, differentiated mostly by the probabilistic nature of generative AI. Yet this is merely the beginning. Emerging AI systems are explicitly designed to adapt their responses to individual patterns, gradually tailoring answers, tone and even conclusions to resonate most strongly with each user.

Personalization is not inherently manipulative. But it becomes risky when it is invisible, unaccountable or engineered more to persuade than to inform. In such cases, it does not just reflect who we are; it steers how we interpret the world around us.

As the Stanford Center for Research on Foundation Models notes in its 2024 transparency index, few leading models disclose whether their outputs vary by user identity, history or demographics, although the technical scaffolding for such personalization is increasingly in place and only beginning to be examined. While not yet fully realized across public platforms, this potential to shape responses based on inferred user profiles, resulting in increasingly tailored informational worlds, represents a profound shift that is already being prototyped and actively pursued by leading companies.

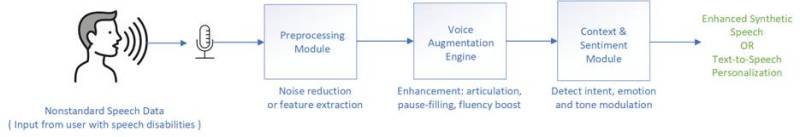

This personalization can be beneficial, and certainly that is the hope of those building these systems. Personalized tutoring shows promise in helping learners progress at their own pace. Mental health apps increasingly tailor responses to support individual needs, and accessibility tools adjust content to meet a range of cognitive and sensory differences. These are real gains.

But if similar adaptive methods become widespread across information, entertainment and communication platforms, a deeper, more troubling shift looms ahead: A transformation from shared understanding toward tailored, individual realities. When truth itself begins to adapt to the observer, it becomes fragile and increasingly fungible. Instead of disagreements based primarily on differing values or interpretations, we could soon find ourselves struggling simply to inhabit the same factual world.

Of course, truth has always been mediated. In earlier eras, it passed through the hands of clergy, academics, publishers and evening news anchors who served as gatekeepers, shaping public understanding through institutional lenses. These figures were certainly not free from bias or agenda, yet they operated within broadly shared frameworks.

Today’s emerging paradigm promises something qualitatively different: AI-mediated truth through personalized inference that frames, filters and presents information, shaping what users come to believe. But unlike past mediators who, despite flaws, operated within publicly visible institutions, these new arbiters are commercially opaque, unelected and constantly adapting, often without disclosure. Their biases are not doctrinal but encoded through training data, architecture and unexamined developer incentives.

The shift is profound, from a common narrative filtered through authoritative institutions to potentially fractured narratives that reflect a new infrastructure of understanding, tailored by algorithms to the preferences, habits and inferred beliefs of each user. If Babel represented the collapse of a shared language, we may now stand at the threshold of the collapse of shared mediation.

If personalization is the new epistemic substrate, what might truth infrastructure look like in a world without fixed mediators? One possibility is the creation of AI public trusts, inspired by a proposal from legal scholar Jack Balkin, who argued that entities handling user data and shaping perception should be held to fiduciary standards of loyalty, care and transparency.

AI models could be governed by transparency boards, trained on publicly funded data sets and required to show reasoning steps, alternate perspectives or confidence levels. These “information fiduciaries” would not eliminate bias, but they could anchor trust in process rather than purely in personalization. Builders can begin by adopting transparent “constitutions” that clearly define model behavior, and by offering chain-of-reasoning explanations that let users see how conclusions are shaped. These are not silver bullets, but they are tools that help keep epistemic authority accountable and traceable.

AI builders face a strategic and civic inflection point. They are not just optimizing performance; they are also confronting the risk that personalized optimization may fragment shared reality. This demands a new kind of responsibility to users: Designing systems that respect not only their preferences, but their role as learners and believers.

Unraveling and reweaving

What we may be losing is not simply the concept of truth, but the path through which we once recognized it. In the past, mediated truth — although imperfect and biased — was still anchored in human judgment and, often, only a layer or two removed from the lived experience of other humans whom you knew or could at least relate to.

Today, that mediation is opaque and driven by algorithmic logic. And, while human agency has long been slipping, we now risk something deeper, the loss of the compass that once told us when we were off course. The danger is not only that we will believe what the machine tells us. It is that we will forget how we once discovered the truth for ourselves. What we risk losing is not just coherence, but the will to seek it. And with that, a deeper loss: The habits of discernment, disagreement and deliberation that once held pluralistic societies together.

If Babel marked the shattering of a common tongue, our moment risks the quiet fading of shared reality. However, there are ways to slow or even to counter the drift. A model that explains its reasoning or reveals the boundaries of its design may do more than clarify output. It may help restore the conditions for shared inquiry. This is not a technical fix; it is a cultural stance. Truth, after all, has always depended not just on answers, but on how we arrive at them together.

Daily insights on business use cases with VB Daily

If you want to impress your boss, VB Daily has you covered. We give you the inside scoop on what companies are doing with generative AI, from regulatory shifts to practical deployments, so you can share insights for maximum ROI.

Read our Privacy Policy

Thanks for subscribing. Check out more VB newsletters here.

An error occured.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login